Let's take a break from the only standing Wonder of the Ancient World left. Yes, the Great Pyramid of Giza is the only and oldest of the seven ancient wonders. The Arab proverb goes: "Man fears Time, yet Time fears the Pyramids." We were at the foot of that, people. Holy crap.

But let's talk about the everyday. Today I have thoroughly enjoyed washing my clothes. We’ve finally purchased a washing machine (make sure you get a good look at the pinkness of our bathroom in the pic). I just did two loads of clothes and hung them on the lines off our back balcony. Here the clothes, turned inside out, will flap against the sandy building and accumulate Cairo odors. They’ll dry quickly in the afternoon sun.

I am proud of my clothesline! A month ago I was dubious about the thought of hanging my clothes seven stories up. How could my jeans get blown around and stay put with only a flimsy plastic clothespin? I learned how, though, from UmmNadia. UmmNadia is our maid.

Yes, I said it. Maid. Go ahead and flinch. Roll your eyes. Gasp that we have hired a maid.

It seems that everyone (who can afford it) has a maid in Cairo. For one, keeping up with the dust is a fulltime job.

Egyptians, or at least the ones I have observed, are incredibly fastidious about cleanliness. If you look at the photographs of apartment buildings from the outside, they may appear dumpy or dirty. Inside, these apartments are spotless. Not ours, really, since I am guilty of a lot of paper piling. Nonetheless: don’t bring the outside to the inside – this is the reigning idea.

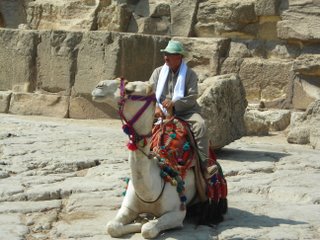

[This is an extreme aside, but I can't help it. Last week as I watched an old white man leaning against a post by the pyramids, and I stared at his sun-reddened belly which he had bared, a belly around which a bright yellow shirt served as an open curtain, a belly on which a round gold chain and mobster pendant dangled, I couldn’t help but momentarily appreciate the way Egyptians cover themselves as a sign of respect.]

There is also the idea that one is actually doing good by employing an Egyptian since the unemployment rate is extremely high. In addition, the Egyptian maid does not consider her job “demeaning” – that’s the word on the street. One of my rich students (they’re all rich, remember), who is the daughter of a member of the Egyptian parliament, informed me yesterday that I should not feel bad about employing a maid. It was hard to swallow this, coming from a politician’s daughter.

Regardless, I fight with myself thinking about whether or not it is OK for me to have a maid here. And it's true that all of the arguments I have against it have to do with the following value -- do it yourself, lazyass. Not that I've ever truly had to work a day in my life, but still -- that ideal is embedded. They say you can spot an American tourist immediately because he will be the only one carrying his own luggage. I don't know how accurate that is. But when we rolled into the airport and people handled my luggage all the way to the apartment, my eyes stayed glued to my stuff. Point? The way Egyptians wrap their minds around the concept of the maid is inevitably different than the way I see it, I believe. I’ve heard, also, that Americans are sought-after employers because we pay more and abuse less. Plus, when we leave here and “fire” our maid, we are expected to give her two months pay beyond the last month she works for us, so that she has a chance to look for another employer.

OK, whatever. So we have a maid. It is still a bit weird after a month. I feel bad sitting in my chair prepping for class and having someone clean all around me. I felt bad the day UmmNadia brought in laundry detergent and proceeded to wash my, er, intimates by hand. I tried to protest, making a repulsed face at my underwear and waving my hands, and she basically pushed me aside and said, Nothin’ doin’. Well, actually, she said something in Arabic that I did not understand, but I got the gist from her spot-on hand signals. We do a lot of pantomiming and giggling at each other. She does make an effort to teach me the Arabic words for certain objects, and then I tell her what they are in English, and we nod and smile and forget the words in five minutes. James started giving her the thumbs-up a lot when she asked something, so now she employs that gesture frequently.

UmmNadia’s name means “mother of Nadia.” So, here, my mom would be UmmAmanda. UmmNadia comes twice a week and spends 3-4 hours in our apartment. When we are here, she says good morning and calls us “doctor” and “doctora.” She starts in the kitchen and washes every dish. She sweeps and mops every floor. She scrubs the bathrooms. She dusts. She wipes down the balcony windows, picks up the rugs and shakes them out, takes out the trash, and moves certain things around if it’s clear we don’t know where we should put them. She picks up and folds errant clothes.

Whenever someone from the university comes to fix something (which seems to be happening a lot: for instance, a funky smell protrudes from one of our toilets at intervals, and they say they fix it, and then the next morning there that stench is, wafting about again, and you have to start asking yourself if it’s just you), she watches them like a hawk. She scolds them if they seem to be dirtying anything or aren’t being careful of the furnishings. A lot of clucking between servicemen and maid goes on. Today I realized that she was telling them that the doctora doesn’t understand Arabic well.

I like having her here when other people are in the apartment. I know this seems weird coming from me, but the service guys prefer to have UmmNadia here too. They are obviously uncomfortable coming into the house without James being present, and that discomfort just displaces itself onto me.

After her first day of working in our apartment, UmmNadia told the dean of our school that James and I “are her children.” I need stuff like that. Yes, indeed, we have a maid.

Amanda