I must say that I was plagued by a certain air of familiarity when we visited the pyramids at Giza yesterday. I felt very much as though I had seen them before. This was not such a big problem for me, though, as I was still awed by the sheer immensity of the structures themselves, and by the absolutely crazy sight of Egyptian hawkers and vendors racing across the rocky desert floor, trying to make a few LE off the rich foreigners.

The grounds of the pyramids are large enough for several parking lots, each large enough for a few dozen tour buses. From one bus you might witness the emergence of a stunned gaggle of geriatric Americans, the old ladies wearing flower-patterned denim hats with a little bow up front, so cute. From another bus might come an extremely enthusiastic group of Asian tourists, hopping gaily across the sandy embankments, posing proudly before the Great Pyramid or the Sphinx, laughing heartily as they view their photographs. You might also see an odd assortment of Europeans ranging from Italian to German to Spanish, clearly distinguished by their garish and scant clothing.

These tourists begin their trek from the bus to the pyramid itself, a trek of perhaps a hundred yards. They are met by a phalanx of vendors, converging from all directions, selling everything from little glass pyramids to plush camels to books of postcards. Their favorite ploy, I soon discovered, was to hand you something and say it was free, a gift for visiting their country. Then, so engaged, they might ask you where you’re from. America? Well then, hi-ho silver it is. No, really, keep the pendant, it is free. Would you like a photograph? Here, give me your camera and I will take. Free!

In one case, a man handed M and I pendants for a necklace, insisted they were free, then wrapped a red and white turban over my head. “You look like Arafat,” he said, at which point I made the mistake of laughing, which encouraged him. He got M to take my picture, then he wrapped the same disgusting, sweaty turban around M’s head, and she, annoyed, also submitted for a photograph. Then he asked for money. No money, I said. “Give me back pendants,” he said, and off he went across the desert with my free gift.

In another case, a police officer, clearly dedicated to his solemn duty, also took my photograph, then wanted money. I said I had none, so he very quickly zeroed in on the Uniball pen in my pocket. So long, Uniball!

Sometimes children would approach, smile cutely, and open like an accordion a booklet of postcards, all connected at the perforated edges. One little girl did this for me. “No thanks,” I say, and she’s gone. Behind me I hear her mutter, “Worthless American.”

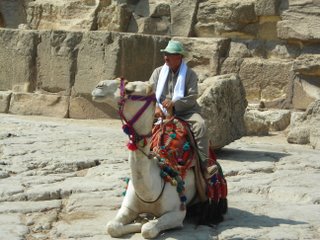

It’s worth reiterating that this is not an orderly procession of vendors and hagglers. They have apparently paid a fee and have full access to the site. They appear with little to no warning, striking just as you begin to live your fantasy of quiet, contemplative reflection before the tattered grandeur of the pyramids. That isn’t happening. You have to say no at least three times, and you must be ruthless—they prey on politeness, on our obligation to respond when spoken to. When one is gone, another one will approach, usually from another angle. Sometimes they offer free camel rides—without saying that they will charge 50LE to help you get off the animal, or that they will trek you far into the desert and charge you a bundle to be guided back to civilization.

I don’t really consider the tourist trade much of a detraction from the experience. I actually think it enhanced it. On the ground you have aggressive Egyptians, coaxing money from the pockets of unsuspecting tourists. And all around, you have one of the most fascinating sights one can ever see. The proximity of these juxtaposing situations has quickly become a trademark of Egypt for me. Grandeur and kitsch can be neighbors in the same building.

* * *

As for the pyramids. They are truly stunning, even if you have to do some brainwork for their full gravity to render. Each stone in a pyramid weighs, on average, 2.5 tons, although some of them weigh 15 tons. This means that the largest pyramid at Giza can weigh six million tons. And it’s a marvel of engineering, too: the weight of the structure presses either inward or downward, stabilizing it. One must also remember that it took peasants perhaps twenty years of hard labor to build these structures, which is a testament to tenacity and longevity and purpose. These are startling facts—I remember reading about them in some history class or another. But, for me, the immensity of these facts, these feats, registered fully only when I stood before one of these wonders.

I was particularly thankful for the quality of effective engineering when I made my trek into the Pyramid of Chephren. Not for the claustrophobic at heart. First, you pay 20 LE for a ticket inside. Then, the man by the entrance takes your camera because you can’t photograph the inside (when you depart, the man will return the camera but request, with a sly smile, a tip). For some reason, I expected the entrance to be upwards, where I saw some tourists climbing. In reality, the entrance emerges at the bottom of the pyramid, and you must take a steep causeway to the base of the pyramid. And then you must crouch, and enter. As you may know, everybody, I am not a tall man, but even so the close quarters of the tunnel gave me a moment’s cloying panic. You continue traveling down, down, at the same steep angle at which you entered. I’d say this goes on for fifty yards, and then the tunnel opens into a room that smells of piss. You can stand up and stretch, but because it is so smelly and, suddenly, so humid—the limestone walls are damp, and so are your forearms—you hurry on through and reach another tight tunnel, this time an incline. And you travel another fifty yards. At this point, you might recall the six million tons of rock, arranged just-so above your head. And then the tunnel opens into a large, vaulted room. The walls are graffitied by some British asshole who first discovered this tomb in the 1800’s. On the far end of the room is a stone coffin. It’s open and empty, of course. And the humidity is upon you. A few minutes later, when you finally emerge from the pyramid, the Sahara Desert will feel like a relief in contrast.

My final note is regarding the Sphinx. Perhaps M will add her own impressions. This was the most difficult for me to “see.” I felt very much like I was looking at a photograph; even the photographs I did take look like postcards or pictures from a textbook. This may be owed to the fact that we got very close to the Sphinx, which is not as large as I thought it would be, and that the viewing site is largely devoid of the hawkers and vendors that gave the Great Pyramids, shall we say, a modern flair. It may also be that the great Sphinx of the ancient world looks down upon a Kentucky Fried Chicken, just a few hundred yards away.

Ramadan is upon us.

James

5 comments:

Great Pictures and stories - keep them coming.

Love

Mom

awesome pics! sounds fascinating.

Your pryamid experience would be perfect for a literary journal. Write it! And then mention me.

We're curious: who are you, Ginger?

I think Ginger likes being mysterious.

Post a Comment