After being two of the thousands of people stuck in the London fog, we finally made it home just before Christmas, where we came bearing Egyptian, British, and duty-free gifts. Now that all the gifts have been opened, I thought I would write about our trip to Khan-il-Khalili.

Khan-il-Khalili is an ancient marketplace in Islamic Cairo. The Khan is probably the second largest tourist site in Cairo, after the Pyramids of Giza. J wrote about Islamic Cairo in the last entry, but let me just say that it is like a step back in time (excepting the ubiquitous motorists and the flashy gifts made in China). The best way to get to the Khan is via taxi. We chose to bring one of our Egyptian friends, Ahmed, thinking he might be a handy translator and buffer. (Turns out Ahmed, who is a suburban kid, hadn’t ever been there, and he was mistaken for a tourist almost as much as we were.) We were let off amidst speeding traffic at a green footbridge, which you cross to enter the main part of the Khan. We weren’t sure at first that we were in the right place, but we knew we were golden when we spotted a white lady with whiter hair wearing salmon-colored culottes.

We turned onto a narrow path that was unwieldy with piles of trash and dirt. Scrawny cats picked through the rubbish. To either side, several small shops belched out smiling Egyptian men who proclaimed, “Welcome in Egypt!” There were several hookah shops crammed next to kitsch – glass pyramid trios, pharaoh statuettes, amulets to ward off the evil eye, wooden boxes with Islamic designs representing eternity. There were many gold and silver stores, and other places selling precious stones, most of which are imported since Egypt has been mined to exhaustion. Several antique shops sported beautiful lanterns and dusty relics that looked as if they should have been piled in a barn. Here we found a similar sort of hawking as went on at the pyramids of Giza, though not nearly as persistent or irritating. Men walked out of their shops and promised, “Everything is free!” It seemed pretty tame to us, but perhaps we were simply more prepared for it, and we had a few more polite Arabic phrases under our belts.

We picked our way around trash as the paths became increasingly more winding and shadowed. Men and boys, hauling carts and carrying sacks many times their weight, pushed their way through the crowd, giving short whistles to indicate that they were coming. We learned to move quickly because they had no intention of stopping. (Later, Ahmed got smacked by the side mirror of a car as it passed. Many of the side mirrors here fold back, and that is what this one did.) One of the men said in Arabic, “Watch your back, woman!” just before he swept by me with what looked like heavy sacks of concrete mix over his shoulders. The further in we went, the dustier and mazier it got. Motorcycles sped through, as well as trucks spewing fumes and hip-hop. We asked for directions a few times and found people offering to share their food and drink.

Finally, we found the place I had been looking for: Casa Fernando – a papyrus shop owned by a petite man named Mohammed who speaks Spanish. He was wearing a denim shirt and chewing a small piece of gum. We informed him that one of our friends had recommended the place. He chewed suspiciously, looked us up and down, then invited us inside his shop, which contained stacks and stacks of papyrus with questionable stamps of authenticity. Two boys were arranging sheaves of papyrus on the floor, and Mohammed sent one of them off for drinks and made us sit down in chairs with seats the size of half my rear. They came back with a tray holding Lipton for James, water for Ahmed, and cold hibiscus tea for me. Then Mohammed pulled out a stack of papyrus and began rifling silently, tossing pieces haphazardly to the floor when I shook my head no. We were looking at dark brown papyrus on which there were traditional paintings of ancient Egypt – the papyrus was framed and supported by jute.

Once I started to show my interest in a few, the bargaining commenced. The first thing Mohammed did was quote a ridiculous price. Being somewhat stingy all my life, I was unimpressed. Then I offered a price I considered to be more reasonable, and he looked at me like I was crazy. “This is very old,” he said rather irritably. “That’s too expensive,” I said, wondering just when that paint had dried – was it last week, or last month? It was a lovely little dance. In the end, I got “ripped off,” but I managed to be firm about what I was willing to pay, and when it became clear I wouldn’t budge (to the point of my putting the papyrus on the pile on the floor), Mohammed gave me the price I had eventually quoted. It was great fun.

Tired of the Khan, we forced our way through a much more crowded area on the other side of the street. To each side in the narrow alley were all matter of fabrics – women’s clothing, blankets, rugs, etc. We had clearly left the tourist zone, as there were no culottes to be seen. We paused in a more open area where, in the span of a few minutes, we watched a motorcyclist ram through a crowd and a flock of sheep barrel past. Up to this point, I had been suppressing all references to misinformed films about the Middle East but could not help but remark here that this could have been the setting for the part in Raiders of the Lost Ark when Indiana Jones shoots the sword-wielding man in the streets of Cairo.

This open area brought us away from the crowded marketplace and into the streets of Old Cairo. We immediately found ourselves walking through a traffic jam, where a donkey pulling a cart leaned its head into the back of a honking Nissan truck. In one shop, a man made cast iron skillets, while next door another man wove baskets. Almost every shop, emptied of patrons, boasted beautiful handmade items – from intricate wooden chairs to walking sticks. I saw just one store that was full of people – this store had enormous sacks brimming with spices and herbs – ginger, cumin, hibiscus, mint. We stopped at a small grocery store for a drink and had to stay there with our glass pop bottles until we finished and could return them, and, as we sipped, we surveyed the place. Out on the street, the donkey still leaned its head against the Nissan, and horns continued to honk. On the way back to the main thoroughfare where we would catch a taxi home and pick up some roasted corn, I witnessed a man leaping onto the hood of a moving, honking car. Ahmed and J were ahead of me, and they didn’t hear me gasp. They also didn’t see the driver of the car laughing, or the man on the hood guffawing, nor the man who made cast iron skillets chuckling and shaking his head.

Thursday, December 28, 2006

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

On Saturday, we took a university-sponsored trip to Islamic Cairo. I know what you're thinking: "Really, isn't it all Islamic Cairo?" And that would be true, from a certain point of view. But Cairo is a very ancient city, and each neighborhood embodies some sort of historical period. Zamalek, for instance, is not only the "exclusive" part of town, but it's also one of the most recent: Gezira Island only firmed up enough to become inhabitable in the 19th century. Islamic Cairo, which is in reality on 5 or 10 miles from where I currently sit, was once the ancient center of town and the center of Muslim life in the city. We walked down a narrow and boisterous street that was once the main street of the city, running from north to south (the city didn't actually approach the banks of the Nile until more recent times). Today there is barely one lane, even though it is apparently a two-lane road, given the traffic in both direction. Trucks, motorcycles, horse and donkey carts--you name it.

The first and largest thing we did was visit the Mosque of Sultan Hasan. I don;t now much about the guy, but his story has an interesting end. Apparently, he constructed the grand mosque that bears his name. Unfortunately, poor Hasan was never buried in his own mosque. He was murdered while out in the desert and his body was hidden, and to this day nobody knows where he is buried. To this day, Muslims use the story as a fable to warn their children against greed and hubris.

Two of the pictures direcly above this section of the post are pics from the mosque. I was struck by the absolute quiet of the place (excepting the children who had tagged along), the hushed reverence of a group. It reminded me of visiting grand cathedrals in England: Canterbury Cathedral comes to mind. Also Stonehenge. I'm not a religious fellow, but certain places have a shine to them, and big old churches and mosques have that kind of presence for me.

One difference between a church and a mosque--and there are many--was the amount of open-air space in the mosque. Churches generally are closed structures. Mosques seem to revel in the open air, especially as a place for worship. You can see this in one of the pictures above, as well.

A lot of the professors who went on the trip have children, and these children were our constant companions throughout the day. Most parents let their children traipse freely among us. Only one parent felt compelled to scold her child, but she was only mad because he did something that got his hands dirrty. "You wonder why you keep getting these diseases!" she said.

The little girl above was quite the ham. She skirted that delicate line between charming and annoying, never quite tipping the scales into annoying. At least for me. She wanted her picture taken, a lot. I never could figure out who she belonged to. I finally acquiesced to taking her picture when she picked up a colleagues backpack. Little girl! Oversized backpack! (Containing expensive computer equipment.) How cute.

And finally, you see me. I actually felt a lot worse than I look in this picture. Notice two things. First, I am wearing a new shirt I had purchased a few days earlier at a shop on 26th July St. The shop is named Dandy. The tiny place was staffed by three nice men who asked M if I was her brother when I retired to the changing rooms to try the shirts. I don't think they meant any harm. It's just normal (see: green card). Second, see the woman with the cell phone? She was like that all day. The damn thing kept going off. I think I was trying to look pensive in the picture, but as I look at it again, I can't help think I was just annoyed at her.

James

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

It’s raining! We’ve thrown open the windows. The air is cool and even slightly fresh. Down below, the street is covered with water – there are no gutters, which tells you how much it rains here. It’s the second time it's rained since we’ve been here – and the first time was for a span of ten minutes. J just pointed out that we are able to see a building in the distance that has never been clear.

Last week the bawaab brought us the census survey. It felt strange and rather exciting to fill in the “foreigner” bubble. It felt doubly strange to give the survey, complete with an estimation of our annual salaries, back to the bawaab rather than an official census taker. As we ready for a visit home, we’ve been thinking a lot about the aspects of Egypt that intrigue, baffle, irritate, and amuse us. Today I’ll focus on the good. The food. Ah, how I love food.

Let’s start with the vendor of sweet potatoes, typically a man in a gallibeya pushing a cart down the street. There is a smoking barrel of an oven on this cart that looks like a chimney. In this oven, sweet potatoes steam and smoke. As the vendor rolls the cart down the street, occasionally setting up on corners, people buy a potato or two for a pound. He wraps it in newspaper and hands it to the customer, who eats it as is. Sometimes the vendor stops and peels blemishes from the raw potatoes before putting them into the fire. A wintertime treat – cheap, easy, delicious, calorie-rich, warm.

Then there is koshari, another carb delight – a big bowl of macaroni, rice, vermicelli noodles, lentils, chickpeas, fried onions, and a bit of tomato sauce. There are numerous koshari restaurants around, but the one we like gives you a little plastic bag of vinegar sauce and a container of hot sauce, and this really makes the meal. There is a man in charge of tying up the bags of vinegar, and he does so between pulls on his cigarette. Six pounds for two enormous bowls.

As for the fruits and vegetables, they are almost always delicious. Cucumbers are small, crisp, and available year round, as are tomatoes, which vary in taste but are much better than the nonentities we buy in the winter in the Midwest. I buy yellow peppers, which are so expensive at home, for a few pounds. Onions and garlic are sweet and fragrant. The cantaloupe here has the rind of the cantaloupes at home, but is green like a honeydew on the inside. I could go on and on. I remember the first few disorienting days I was here – when we passed a green grocer, flies were swarming the grapes, the money was confusing, and the shop was situated next to a pile of trash sweating in the heat. It seemed at the time that I might never eat anything nutritious again. How wrong I was. In fact, we’ve come to find that even the canned or frozen foods often have no preservatives, or “without conservatives,” as the mozzarella cheese package says in the photo above. This is not to say that we are totally naïve. Pesticides are used; food sitting out all day in the street cannot help but absorb the immense pollution, etc. I wash everything with soap and water. Some people go so far as to put it in diluted bleach. All of this does not diminish the fact that the fruits and vegetables are delightful.

Our first real experience with an Egyptian meal was at our friend Ahmed’s home. Each time a space would open up on our plates, Ahmed’s mother would hurry over and spoon more on. “You’re not eating enough!” she said. It is common for Egyptians to do this to you, and I have been warned that you must strike a delicate balance – you must eat enough, but you must not eat too much. If you do not eat enough, they will think you are rude. If you eat too much, you are a pig.

I had explained weeks before this dinner (so as to lessen my offense) that I am a vegetarian. Vegetarianism often baffles Egyptians. It did not make sense to Ahmed’s family, and they questioned me about it off and on through the night. In fact, Ahmed seemed a bit disappointed in me when I thought I was being polite in telling him in advance. I brought out my "I grew up on a farm and we would eat off one cow and one pig for a whole year" story, which seemed to improve my standing. Now that I think about it, though, I did mention eating pork to a group of Muslims. Nonetheless, vegetarian dishes appeared – steamed vegetables, bean salad, potato salad, coleslaw, pastries stuffed with spinach and flavored with lemon, a casserole dish of Chinese noodles and vegetables, rice with vermicelli noodles, and several others. Delicious! The amount of food was dizzying. Dessert consisted of a homemade cheesecake, a fancy store-bought chocolate cake, and a chocolate mousse with walnuts.

Later, Ahmed’s mother and father brought me into the kitchen to show me their fuul pot and explain how to make fuul. The fuul pot (at least the smaller family-sized version) resembles a carafe, and it steams and simmers all day. A regular fuul pot is enormous with a thin neck, almost like a symmetrical gourd. I cannot remember the exact recipe for fuul, but it involves hours of cooking after hours of soaking. It was the way they told me about it that was so beautiful. Ahmed’s mother pulled out a handful of beans to show me as she explained how long to soak them, when to change the water, etc. She moved these beans from hand to hand as she spoke, and she made me grab a handful of the beans as she explained their properties. Ahmed’s father picked up some lentils and broke one of them with his teeth to show me the inside (a small bit of lentils can help the flavor of fuul). Then he lit the gas stove and demonstrated the exact level the flame should be at. They did not simply tell me how to do it – they acted it out. The fact that I can’t remember the recipe only reflects badly on me. Fuul, though, is another typical Egyptian dish made of slowly cooked fava beans. The flavor is mild but hearty, and can be paired with lots of other foods but is mainly eaten with bread.

The meat in Egypt? J can tell you all about it.

I have always had a simple taste in food, so it should not be surprising that I love the staples of this country. Actually, I've heard and read many complaints about Egyptian food, all lodged by foreigners. The odd complaints of resident Americans, as a matter of fact, is another Egypt thing on my brain. Anyway, rest assured that the mozzarella was lying -- there are, in fact, some conservatives in Egypt.

In writing this, I have realized it is time to get some groceries. Here is a sad little picture of some of the food in our apartment. You will see a can of strained fuul on the left and spicy peeled medammas (another kind of fuul) on the right. Of course the canned stuff is not worth mentioning after having the real thing. Enjoy!

Amanda

Monday, November 27, 2006

To get to the university I take the Zamalek shuttle, which departs each half hour from the dormitory, a good five-minute walk from our building. Some days the shuttle gets to the university in little more than ten minutes, but many times there is some significant delay. A taxi, for instance, has stopped his car on a main thoroughfare. He’s talking to a man on the side of the road—perhaps about a fare. Or perhaps the main is his cousin, or his sister’s husband. Their animated discussion could be about most anything. It’s also likely that we will meet some traffic problems at the “stoplights” at the European-styled roundabouts, which usually do little more than flash yellow, yellow, yellow, while a team of police officers give the signals—which amount to little more than curt gestures I still do not understand. Sometimes the traffic police are chatting with one another and forget the deft timing it requires to keep traffic flowing, but motorists are happy to honk and remind them.

To get to the university I take the Zamalek shuttle, which departs each half hour from the dormitory, a good five-minute walk from our building. Some days the shuttle gets to the university in little more than ten minutes, but many times there is some significant delay. A taxi, for instance, has stopped his car on a main thoroughfare. He’s talking to a man on the side of the road—perhaps about a fare. Or perhaps the main is his cousin, or his sister’s husband. Their animated discussion could be about most anything. It’s also likely that we will meet some traffic problems at the “stoplights” at the European-styled roundabouts, which usually do little more than flash yellow, yellow, yellow, while a team of police officers give the signals—which amount to little more than curt gestures I still do not understand. Sometimes the traffic police are chatting with one another and forget the deft timing it requires to keep traffic flowing, but motorists are happy to honk and remind them.And then there is the sheer audacity of the number of cars. It amazes me that this city moves at all, since routinely there are disorganized masses of vehicles trying to fit into increasingly tight bottlenecks, honking their horns (though not necessarily in anger…there is a complex code to honking, such that a honk can come to mean anything from “Fuck you” to “I will see you tonight and yes, yes, I will bring the Balady bread and you shall bring the tea. And peace be to you! To everybody! I love this life!”). I’ve learned since being here that lanes are a luxury—every inch of road space is needed here.

This is what happens when a head of state passes through town.

To give you an image of Tahrir Square, you can call it a poor man’s (I do despise the aptness of that cliché) Times Square. It’s the unofficial center of Cairo, with the famed Egyptian Antiquities Museum, the Arab League offices, the AUC, an always-busy mosque, and a Hardee’s, along with a lot of super-sized advertisements displayed on the roofs of the apartment buildings overlooking the square. There is a large, tiled area populated with park benches, across the street from the university, and a few lame green patches, also decorated with park benches. There is apparently a subterranean parking garage that has been full, with a lineup of vehicles waiting, every time I have passed by it. There are also always some conspicuous tank-looking vehicles that house military police, who are present in and around Tahrir Square because this is the site of many demonstrations, and when demonstrations occur around here, the military gets involved, with the government’s blessing. Such is the nerve center of Cairo.

Now, imagine that all of it has been eliminated. Well, almost all of it. No cars, no pedestrians, no traffic, no honking or Arabic cursing, and, strangely, almost no noise. The square was populated with people, to be sure, but they all spoke in hushed tones, seated at the benches or huddled close to one another. Along all the many streets that converge at Tahrir Square, lined up equidistant from one another, were black-uniformed military officers. Interestingly, they were facing away from the street, facing away from the road that “The Hons,” a.k.a. President Hosni Mubarak, would momentarily be passing through.

I hopped off the Zamalek shuttle and tried to cut across the square and make it to an 11:30 meeting with a student, but I was blocked by an officer, and told by a plainclothesman—there are many here in Egypt (I saw one just today, strutting down the street, a revolver tucked into the back of his pants)--to back off, Jack. So I waited with the whispering Egyptians. They all seemed a little bit nervous. I drank in the beautiful, not-so-polluted-as-usual day, listened to the wind flapping the flags of Egypt that had been placed, I now noticed, at several intervals throughout the square.

For all of this, the president’s passing through was uneventful--which is, I imagine, the purpose of all this hullabaloo. Still, I was struck by the intimodating display of military presence as a sign of respect to the president—or an expression of his power (after all, everybody seemed nervous). A few motorcycles came through, then a convoy of SUVs, then a few more cars, and it was over. Traffic resumed. Almost immediately, the honking started.

* * *

The other night, as M and I were settling in to watch Lord of War on this very same computer I’m now typing into, our viewing was interrupted by some severe honking down below, on the street. Honking is not unusual in Cairo, but we have become accustomed to its particular rhythms and cadences—it’s a confusing code we don’t actually understand, but we understand the noises of that code. What we were hearing was your basic frustrated honking. Naturally, we paused Nicolas Cage in the middle of another dryly delivered line, and opened our windows, and looked down.

Our street is narrow, and at night cars are typically double-parked, so it’s difficult for cars traveling in opposite directions to pass one another. I believe I have written before of the artistry of it. On this night, no artistry to be found. We had two cars facing one another, not enough space on either side for them to steer around one another. Neither car was moving. The car to the left was traveling in the direction least often traveled on our road—though, to some extent, all roads here are equal opportunity roads. But there were no cars behind this car. He was alone. He seemed to be causing trouble for all the cars going in the other direction, not only those cars who wanted to continue on down Bahgat Aly St., but who wanted to make turns at the convoluted and dangerous intersection at the end of our block. None of this was possible. Unfortunately, the ancient police officer whose charge it is to direct traffic at this intersection, or to nap, was long gone. And the guard at the Chinese Embassy, who we watched observing this action, was not interested in involving himself.

Instead, others got involved. A trapped cab driver got out of his car and walked up to the car at the left, who was apparently the one causing all this trouble. But the driver of that car was not to be moved—unless it be forward, we assumed. It was the only answer that made any sense at all. In any event, the taxi driver gave up trying to reason with the driver of the car and went back to his cab, and we didn’t see him again.

Others felt the need to involve themselves. The protégé of our bowaab, a young man who is a bowaab-in-training (we think), tried to reason with him, even trying to move parked cars (they’re usually in neutral, so people can move them as necessary) to accommodate what must have been the driver’s demand for a primo parking spot. But the space in front of our building was not primo enough, it seemed. Some other unhappy drivers left their cars, and in a manner that became increasingly animated, pleaded with the man to move. After all, I could imagine them saying, you are now making life miserable for the occupants of some twenty vehicles. Why not back up and let us through?

Not to be. In fact, the passenger of the car took the liberty of lighting a cigarette and, I imagine, smarting off to one of the increasingly upset people standing all around the car—so, naturally, the man who had been the recipient of the smart comment smacked the cigarette out of the hand of the passenger. The man in the vehicle must have responded with angry, and not smart, words, for the man in the street leaned into the car and began punching the passenger. So the driver finally emerges, ready for action...and promptly finds himself on the ground getting kicked and punched by a couple of other men. I must say that I found this little bit of violence somewhat satisfactory, since, although M and I had been laughing at the complete inanity of the situation, I was also annoyed that somebody would be so hard-headed as to insist on not moving, thus inconveniencing a great many motorists, and delaying my viewing of Lord of War.

I can say that I found the fisticuffs satisfactory because it all turned out to be harmless. As soon as the fighting started, the main perpetrator of the violence ran away—after getting in one more good punch on the passenger—and a bunch of other men—drivers, passers-by, our bowaab-in-training, did all that they could to diminish the violence, calling for peace. Initially, this didn’t work, as the driver returned to his car only long enough to move it diagonally across the road, which served as a symbolic fuck-you to…I don’t know for whom. But whomever it was intended for, there you go. But the man who had kicked him and punched his friend was gone, and the driver was now a fool, and he had no option but to do what he had been urged to do all along. He returned to his car, backed up, and disappeared down the street. Two minutes later, traffic was back to normal. It was like nothing had happened in the first place.

* * *

So sorry to those of you who have checked When in Cairo faithfully these past two weeks, only to find no update. M has offered to write an entry, but it’s been my turn to write, and I haven’t, so all that big heap of blame can go right here. Since the Eid, it has been busier at school, and I have been fighting off another sinus infection (vanquished now, it seems). Anyway, we will do all we can to post a few more times before making our way West for the long holiday to come.

James

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

Sunday, November 12, 2006

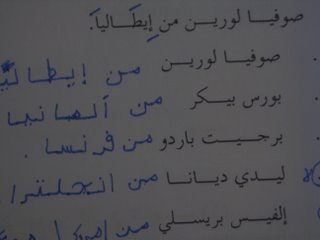

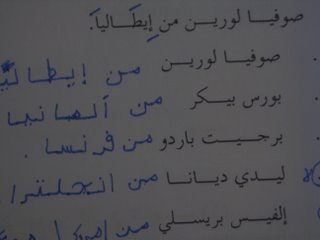

For a little over a month, I’ve been learning Arabic twice a week through a university tutor. I thought I was just going to be learning to get by – some daily phrases that would help me barter and say hello and carry on a basic conversation. But no! We will learn to write before we can learn to speak! Then you can sound out words, even if you have no idea what they mean! I looked at the traditional alphabet that first day of tutoring and knew there was no hope. A little over a month later, I have made it through 70 pages of my study book and have just learned my first Arabic verb. My ambition to be speaking sentences by December has been doused by reality. I am truly humbled by the difficulty of this language. I feel like a baby, barely literate, being coddled by the nice women in the Arabic department who hold my hands and sugar me up when I am assigned to say something simple to them at the end of my lesson.

Many of the words are gendered. The words go from right to left. The possessive form is as difficult for English speakers as articles are for those learning English. The letters look different depending upon where they appear in the word, and some of them can connect to letters from the right but will not connect with letters coming after. When I make the mistake of trying to connect these letters, my tutor sternly says, “I told you! No link!” He is a stern man who answers his cell phone when I am sounding out words. The impromptu “No link!” has become part of our household lexicon.

I am humbled when my tutor shakes his head and says, “You didn’t study!” after I have spent hours the night before trying to understand my homework. But it is true that I can read now. It takes me twenty minutes to read a sentence, but I can read!

Since I am usually in Zamalek or at the university, I am around people who will answer in English even if I try to speak to them in Arabic. When we went to Bahariya, Samir was the only one we knew who could speak passable English. We also met a little girl who was very good with English. Other than that, with no alternatives, I found myself understanding and speaking more than I actually thought I had retained. Immersion. Of course.

There was one other man in Bawiti who knew enough English to draw a tourist crowd. Bayoumi was the owner of the Popular Restaurant, located across the street from our hotel. The restaurant consists of a latticed area holding the kitchen and one dining table in a building that looks like a cheery machinery shed. Outside are two long tables with colorful plastic chairs. The town of Bawiti is quite dusty, but the tables were impressively clean. The restaurant cooks a set meal a day. You get a pile of bread and several dishes – noodle soup, pickled lemons (an acquired taste) and olives, rice with vermicelli, stewed beans, potatoes, stewed peppers, eggplant, chicken, etc. The Popular Restaurant is also one of the only places in town that serves beer – Sakkara Gold for LE 15. We ate at the restaurant on our first night, and I managed to tell Bayoumi in Arabic that I was a vegetarian. His response gave me enough courage to keep trying out the language.

Everyone in town gravitated past this spot, where Bayoumi held court, drinking Bedouin tea, smooching children, and shouting to everyone he knew. He immediately made friends with J and greeted us loudly each morning when we came outside. He would say, “You come here for dinner? Hotel food no good!” One day as we came back from a walk around town, he sprang from behind a parked truck trying to scare us. Another day, when we had stopped in for a drink, he walked by and smacked us both on the foreheads. When I later asked Samir what the slap on the forehead meant, he said, “It’s OK,” his refrain, so I still don’t know if that old man was being affectionate or really just thought he could get away with smacking a couple of Americans on the head.

Every time Bayoumi saw us, he would yell, “Bush! No good!” and proceed to make a spurty noise to accompany a vigorous thumbs-down. Then he would say, “Americans! Good!” One night he and James ran through a lengthy list of American presidents, and Bayoumi gave his spurt or his thumbs-up. Kennedy! Good! James then listed off the Egyptian presidents he knew, and Bayoumi had nothing but praise. Later, Bayoumi leaned over to me and said secretively, “The American dollar. Very good.” Bayoumi’s photo is below. What you don’t see is that he is holding my hand, and it is very cute.

I have strayed from the main topic, but when I think of Bayoumi I think of the language – he had command over enough English and I had command over enough Arabic for us to have a good time, for us to avoid sitting uncomfortably in silence.

Now I have become addicted to learning Arabic, despite my slow learning curve. I am starting to hear words separated out when people speak around me. Signs and conversations are no longer indecipherable blurs but threads peppered with understandable notions.

I’ll close with a story about getting lost in Cairo this morning. You see, I had to have a blood test and other stuff to get my work visa, and today I was wandering about looking for the lab that turned out to be in a nameless building and in a clinic that made me yearn for the sealed buckets of needles in doctor’s offices at home and for the flawless blood-taking ability of Sonita, a nurse who works with my mom. But I walked right past this clinic without seeing it, just a few blocks from the university, and stepped into another realm. Donkeys, and men smoking sheesha, and more completely covered women.

As I walked by what seemed to be a school, I looked over to an alcove which opened onto a courtyard. Several men were standing around, as usual. When they spotted me, they shouted welcome and ran out to get me and brought me into the courtyard. Clearly, I had looked lost. One of them said, “I can understand you!” in English and then when I started to speak he said he could only speak French but he would take me to the man who spoke English. The man who spoke English looked like a promising fellow, with spectacles and a newspaper, but he too could not understand what I was saying about finding a lab. All of the men were speaking and jostling, and for a moment I remembered the stories about women getting harassed after Ramadan by herds of men. After all, they had brought me in this strange space, and the last woman I had seen was at least a block away. But, seriously, they were wearing old man trousers, and I never felt freaked out. Anyway, suddenly I spoke some Arabic to them, and a little more, and a little more. Each time I said something in Arabic, they cheered. I have never been to a country where attempting to learn the language is so highly praised at the slightest word. Turns out it did me no good because they only understood that I wanted to go to the university and not the university lab. Guy Who Speaks French jauntily put out his arm for me to take and led me toward the university, right back where I had started.

I’ll leave you with a photo from my workbook. You can see my freakish writing next to the neat printed Arabic.

Many of the words are gendered. The words go from right to left. The possessive form is as difficult for English speakers as articles are for those learning English. The letters look different depending upon where they appear in the word, and some of them can connect to letters from the right but will not connect with letters coming after. When I make the mistake of trying to connect these letters, my tutor sternly says, “I told you! No link!” He is a stern man who answers his cell phone when I am sounding out words. The impromptu “No link!” has become part of our household lexicon.

I am humbled when my tutor shakes his head and says, “You didn’t study!” after I have spent hours the night before trying to understand my homework. But it is true that I can read now. It takes me twenty minutes to read a sentence, but I can read!

Since I am usually in Zamalek or at the university, I am around people who will answer in English even if I try to speak to them in Arabic. When we went to Bahariya, Samir was the only one we knew who could speak passable English. We also met a little girl who was very good with English. Other than that, with no alternatives, I found myself understanding and speaking more than I actually thought I had retained. Immersion. Of course.

There was one other man in Bawiti who knew enough English to draw a tourist crowd. Bayoumi was the owner of the Popular Restaurant, located across the street from our hotel. The restaurant consists of a latticed area holding the kitchen and one dining table in a building that looks like a cheery machinery shed. Outside are two long tables with colorful plastic chairs. The town of Bawiti is quite dusty, but the tables were impressively clean. The restaurant cooks a set meal a day. You get a pile of bread and several dishes – noodle soup, pickled lemons (an acquired taste) and olives, rice with vermicelli, stewed beans, potatoes, stewed peppers, eggplant, chicken, etc. The Popular Restaurant is also one of the only places in town that serves beer – Sakkara Gold for LE 15. We ate at the restaurant on our first night, and I managed to tell Bayoumi in Arabic that I was a vegetarian. His response gave me enough courage to keep trying out the language.

Everyone in town gravitated past this spot, where Bayoumi held court, drinking Bedouin tea, smooching children, and shouting to everyone he knew. He immediately made friends with J and greeted us loudly each morning when we came outside. He would say, “You come here for dinner? Hotel food no good!” One day as we came back from a walk around town, he sprang from behind a parked truck trying to scare us. Another day, when we had stopped in for a drink, he walked by and smacked us both on the foreheads. When I later asked Samir what the slap on the forehead meant, he said, “It’s OK,” his refrain, so I still don’t know if that old man was being affectionate or really just thought he could get away with smacking a couple of Americans on the head.

Every time Bayoumi saw us, he would yell, “Bush! No good!” and proceed to make a spurty noise to accompany a vigorous thumbs-down. Then he would say, “Americans! Good!” One night he and James ran through a lengthy list of American presidents, and Bayoumi gave his spurt or his thumbs-up. Kennedy! Good! James then listed off the Egyptian presidents he knew, and Bayoumi had nothing but praise. Later, Bayoumi leaned over to me and said secretively, “The American dollar. Very good.” Bayoumi’s photo is below. What you don’t see is that he is holding my hand, and it is very cute.

I have strayed from the main topic, but when I think of Bayoumi I think of the language – he had command over enough English and I had command over enough Arabic for us to have a good time, for us to avoid sitting uncomfortably in silence.

Now I have become addicted to learning Arabic, despite my slow learning curve. I am starting to hear words separated out when people speak around me. Signs and conversations are no longer indecipherable blurs but threads peppered with understandable notions.

I’ll close with a story about getting lost in Cairo this morning. You see, I had to have a blood test and other stuff to get my work visa, and today I was wandering about looking for the lab that turned out to be in a nameless building and in a clinic that made me yearn for the sealed buckets of needles in doctor’s offices at home and for the flawless blood-taking ability of Sonita, a nurse who works with my mom. But I walked right past this clinic without seeing it, just a few blocks from the university, and stepped into another realm. Donkeys, and men smoking sheesha, and more completely covered women.

As I walked by what seemed to be a school, I looked over to an alcove which opened onto a courtyard. Several men were standing around, as usual. When they spotted me, they shouted welcome and ran out to get me and brought me into the courtyard. Clearly, I had looked lost. One of them said, “I can understand you!” in English and then when I started to speak he said he could only speak French but he would take me to the man who spoke English. The man who spoke English looked like a promising fellow, with spectacles and a newspaper, but he too could not understand what I was saying about finding a lab. All of the men were speaking and jostling, and for a moment I remembered the stories about women getting harassed after Ramadan by herds of men. After all, they had brought me in this strange space, and the last woman I had seen was at least a block away. But, seriously, they were wearing old man trousers, and I never felt freaked out. Anyway, suddenly I spoke some Arabic to them, and a little more, and a little more. Each time I said something in Arabic, they cheered. I have never been to a country where attempting to learn the language is so highly praised at the slightest word. Turns out it did me no good because they only understood that I wanted to go to the university and not the university lab. Guy Who Speaks French jauntily put out his arm for me to take and led me toward the university, right back where I had started.

I’ll leave you with a photo from my workbook. You can see my freakish writing next to the neat printed Arabic.

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

Sunday, November 05, 2006

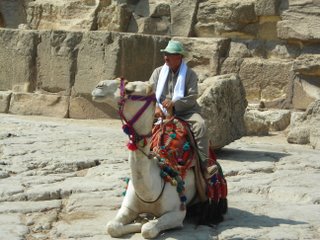

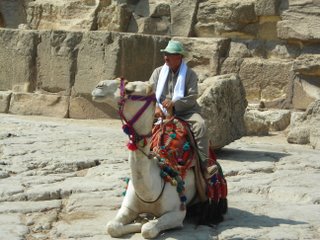

Our first evening in Bahariya, Samir and Mahmoud drove us all over the depression, out to Pyramid Mountain, to a stinky salt lake whose shoreline was caked with sulfur-smelling salt deposits, through a grove of date palms (Mahmoud stopped the vehicle, hopped out and grabbed us some dates…which are, incidentally, perhaps the only fruit M does not like). Then we arrived at the part of our journey where we rode camels. All day, Samir had been mentioning this camel ride, intermittently and vaguely, seeming to oscillate between promising us an adventure and telling us that it would be “okay.” Samir’s English is good, but not so good that he could answer our questions about how long we would be on said camels, and where we were going on them. “It’s okay,” he said, and we shrugged and said to ourselves, “He’s the expert. It’s okay!”

We stopped at a small grove in the oasis, where some Bedouins tended a small herd of camels. We saw camels grazing on the grass that grew, improbably, from the sandy dirt. I will say that camels generally are possessed of a facial expression that conveys bemusement. In truth, they are grumpy sons of bitches.

M was, shall we say, skittish about riding a camel; I took this as an opportunity to put her at ease. I think I shrugged my shoulders and made a strange, lippy frown, and said how everything would be “fine.”

Some of you reading this may recall the ill-begotten horse trail ride trough the mountains of Colorado many years ago. This may have been the final vacation for the nuclear family unit into which I was born, and excepting this horse trail ride, it was quite nice. But the horse trail ride was a nightmare; I was a shrimpy, knobby-kneed, hyperactive child, given dominion over his own horse. We got a couple hours into the mountain trail when it began to hail and we decided to return to the stables. This did not stop each of us from taking quite a beating, to get very wet, and for my horse to get so freaked out that it started walking backwards.

I have never felt the comfort of a hotel bed as keenly as I did that evening.

Back in Bahariya, M initially attempts to convince me to take the camel that has been brought for her. It turns out that this camel is just cranky in the way all camels are cranky, and once she climbs aboard, it behaves very well. My camel is a different story. My camel would rather be grazing with its buddies, and it makes every attempt to wrangle free of the rope that is tied around its head, which my Bedouin guide uses to pull the poor fellow away from his buddies (who are now being shepherded into the stable), and out into a desert flat in the direction of Pyramid Mountain.

Here are things I am observing as the camel waddles its grumpy ass across the desert floor. First, the camel saddle is different than the horse saddle. It makes generous room for the emergence of the camel’s giant, hairy hump, which was pressing uncomfortably into my ass. Second, M’s camel is farting a lot. Also, my camel keeps trying to wrangle free of its ties, and every so often it will release a deep, angry bellow and twist its head, its mouth wide open—full with a green foam and pieces of grass. Then, I look to the left. Before us is a large, empty expanse of the desert floor. The day had been overcast—perhaps our first overcast day in Egypt—but now the clouds have thinned just as the sun reaches a mid-point in the sky, halfway between its noontime apex and the horizon. The clouds were indistinct, just a thin, translucent sheet. The sun spread against this gray sheet, widening, brightening—until there was no sun at all, just an ethereal white light. I suppose I now know why and how those trudging through the desert in Egypt could come to believe in such a thing as heaven.

Such were my thoughts when my camel—remember him?—had had enough of my burden and set about, I’m certain, getting me off his back. For those of you who don’t know, the camel sits in the following manner. There is a moment’s hesitation, a warning, as the camel stops what he is doing and prepares to do…something. For me, the quick onset of the realization that something was about to happen was as strong as the nasty breath and flatulence of the camels themselves. Then, abruptly, the camel bent his front legs and dropped to his knees. This put me quickly at a 45-degree angle in reference to sweet, sweet Planet Earth, which loomed, dangerously now, directly in front of me. Seriously, if I hadn’t been holding tightly onto the saddle, forearms bulging and glistening with sweat, I probably would have been tossed, or met with some other equally embarrassing fate. Fortunately, said forearms were indeed pumping, and I me with nothing worse than rope burn on my palms. And a delightful view of the ground. Then the camel sat down the rest of the way, folding its rear legs underneath, and steadfastly refused to move until our Bedouin guide “encouraged” him by slapping him on his long neck with a pole. So, the camel stood again, reversing the process I just described, and pranced all the way to the drop-off point, with Bedouin guide poking him on the haunches with a long wooden stick. Of course, none of this is quite as good as M’s camel refusing to sit at the end of the ride. She had to jump off.

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Bahariya Oasis – Desert Trip

This is the first post about our trip to the Bahariya Oasis, which yielded all matter of encounters. I’m starting with the second day. After breakfasting on feta, baladi bread, fava beans, and NesCafe in the salmon-walled dining room of the Western Desert hotel, we loaded up in the hotel’s blue jeep and admired the white flames painted on the side. J had requested that awesome jeep from Samir, the manager, and since we were basically the only ones in the hotel, he obliged. We climbed in with Samir and Mahmoud, our driver, who played Arabic music in the car all day and sang nonstop as he whipped around rocks and bumped us through the Western Desert.

Our first stop was an enormous dune not far from town – the culmination of our drive was the jeep picking up speed to make it up to the lower elevation of the dune. A dune is a miraculous thing, but there is not much more I can say except that I collected some beautiful rocks and marveled over the way the sand had smoothed crevices into them.

Next we entered the Black Desert, where the sand was covered with rocks that looked like a layer of pepper from a distance. We stopped at Black Mountain, one of the largest formations, and the rocks here were striking – obviously black, and cut, grooved, shaped by the whims of sand and wind. I climbed about ¾ of the way up the mountain (it wasn’t a big mountain, mind you) until it got too steep for my tennies. J went the other direction, down a path like a spine, picking and tossing rocks.

Again, changes – scrubby plants and lighter sand. Soon Mahmoud swerved off the main road again, and we bumped around for a bit before a large square tank appeared, water spilling into it from a pipe. Next to the tank was a hut, its walls woven with palm leaves, inside of which were mats and woven baskets. When we went to change clothes, I asked Samir if it would be offensive for me to wear shorts, and he said no, "You are free here." Ah, this is where freedom can be found, in a hot spring in Egypt. I wore a huge tee-shirt, in addition to my sprawling mesh shorts, and still I felt a bit risqué until later when an older woman showed up with a bikini bottom sporting her buttcrack. Still, I felt better in my baggy get-up, especially considering the gaze she got from the men folk.

The hot springs were not as hot as one would imagine and smelled of sulfur, but I cannot downplay the fact that this was my favorite part of the day. Water gushed from the pipe and circulated, emptying into a channel that ran to the side and eventually under the palm leaf wall of the hut and through the hut itself. When we pulled up, an old man on a donkey had stopped near the hut, and the donkey was hauling baskets of green on each side of his belly. People were working in a field in the distance, and there was a small group of homes far off comprising a Bedouin village. As we swam, the bikini-ed woman came and left with her posse of Egyptian men, and a group of American tourists pulled up, looked around, and departed.

Then Samir said they would make us lunch. As we sat on the edge of the tank to dry, two little boys walked up and asked for money. J gave them 50p and they seemed thrilled. I tried to speak a little Arabic to them, and they asked me for a pen, which I didn’t have. Kids want pens here. Bring them if you visit. The oldest boy couldn’t have been more than 6; the other was 4 or 5. This was already something we were used to – the kids, everywhere - a subject for another post. The two of them stared, fascinated, until Samir called us into the hut.

Our lunch was set up on a squat round table painted yellow. We sat on the mat-covered floor and feasted on baladi bread, fava beans in tomato sauce, soft feta mixed with tomatoes and cucumbers, tuna (J ate this), chips, Pepsi, and agua. I love me some food. It was so shady and cool in the hut, with the spring running through the channel and the palm tree foundations. When we were finishing up, Mahmoud brought us Bedouin tea in little mugs shaped like pitchers. Indescribably delicious, this tea, with fresh sprigs of mint. Keep in mind that poor Mahmoud and Samir were sitting there fasting, it still being Ramadan for a couple more days. When we finished, we washed our hands and feet in the part of the spring that ran through the hut – there was a bar of soap nestled in the palm tree closest to the water.

We left this tranquil setting and went on to a military stop, where Mahmoud had to give info about himself and say what nationality we were. We had heard from others that you are bound to get a military or police escort if you are an American tourist, and that this escort is like having a big target on you saying, Hey, Look at the Americans!, but we did not run into such trouble on our trip.

We then crossed into the White Desert, another landscape shift, and almost immediately pulled over to see Crystal Mountain, which is more like a hillock made entirely of – you guessed it – crystal. Slivers lay broken over the mountain, but this was the only site with an environmental protection sign, and you know how I am about rules, so none of you are getting crystals. But you may get a rock if you play your cards right.

From here we went off road, eventually coming upon the breathtaking panorama of a valley marking the beginning of the most interesting parts of the White Desert. We stopped here and gazed at the chalklike minerals, rippled like snowdrifts, against the side of the mountains. Then we entered the valley. Some parts of the floor were sheer rock, and Mahmoud took the jeep nearly sideways at the base of formations to stay out of the rock. We entered another large open patch with a white rock floor on which were scattered “flower rocks,” black and round with bulbous protrusions. We stopped here, and Mahmoud, having noticed my penchant for collecting the details of the earth, kept handing me rocks, each one stranger than the next.

The landscape changed again, this time scattered with shrubs and palms, many of them fallen over or dead. Samir said the Bedouins used to live here “200 or 300 years ago.” Samir was a great person to have around, but he was no historian. I soon learned to curb my questions about the history of places and just enjoy them for what I saw. What was clear was that the groves had outlived their usefulness – no water, no human life. We kept passing these old groves and turned onto a rockier landscape, the jeep shuddering as we dodged boulders. Suddenly a real oasis appeared, a small grove of palms with a natural spring. Mahmoud stopped to put water in the jeep. Someone had hung plastic bags of sugar, salt, and flour from the palm trees, which were loaded with colorful bunches of small dates.

Finally, we reached the most eerie and famous formations of the White Desert – mounds at first, like swollen thumbs dipped in salt and sugar. The first stop: “Ice Cream Valley,” consisting of scooped and swirled formations. Eventually, we came to “The Chicken,” which is two formations – one that looks like a flower or a mushroom, and the other shaped like a small hen clucking up at the flower. Both are situated on a round pedestal of rock as if they had deliberately been put on display.

Indeed, that’s the amazing thing about all of these formations – they look as if they, like the Sphinx, were purposely created and sculpted – lions, profiles of human faces, etc. – when the miracle is that they were simply made from erosion, deposits, wind – the whims of minerals and air. I guess a further miracle is that what we tend to see in these formations is ourselves.

The other day I was thinking about this tendency to see ourselves in inert objects and came upon a passage in a book called The Botany of Desire, in which Michael Pollan quotes Emerson: “Nature always wears the colors of the spirit.” In classical rhetoric, “colors” refer to tropes [this trope info was also revealed to me by Pollan], meaning that we cannot see or experience without preconceived notions, past experiences, or expectations coloring what we see. We think these formations in the White Desert imitate us rather than that we imitate them, or perhaps it goes deeper than imitation. The smallest crevice delights us only in that it seems to resemble ourselves and what we know. Sure, the desert was eerie, but the shapes were us – they could only be us.

All of this (with respect to Emerson, Pollan, DeLillo, and everyone else who has had thoughts such as this a million times before, of course) struck me when we pulled up to a formation and Samir said: “The Horse.” Even though I nodded my head in agreement, I could see nothing like a horse. I saw a large base and a smaller craggy bit jutting from the top. Meanwhile, J scrambled up a formation that seemed a bit big for his britches; nonetheless, he made it and paused like Superman surveying his heroics, chalk smattering his jeans. Then I peered at the horse and saw its long neck and its mane, exactly where I had been looking for it.

At this point, I must flash forward to the next day, when we watched the sun setting from English Mountain, a cliff with a crumbling rock house where some Brit used to live. The cliff offers a magnificent view of Bawiti and the sun, pink and dropping until it plops out of sight. We took a few pics before the sun actually set but then just watched the splendor, hands wrapped around our knees. As the sun sank, a woman behind us loudly lamented the faulty lighting of her camera, totally disregarding the miracle of the present because she couldn’t record it as a moment in the past.

Let’s go back to The White Desert, though, where the sun is beginning to set just as we pull up to a formation called “The Mushroom,” which I sit under like Alice, watching the way other formations seem to change with the light, surfacing and submerging. Iftar comes, so Mahmoud and Samir chow. Then back to Bawiti and the hotel – a two hour drive.

We met other vehicles occasionally, which each time involved a conversation of lights flicking on and off: Are you there? Yes, I’m here. Do you see me? Yes, I do. Are you sure? You betcha. And one last flicker upon passing. I might add that no one seemed to have taillights. As soon as Samir fell asleep in the front, Mahmoud lit a cigarette. Later, when he tried it again, Samir woke and made him put it out. Their relationship all day was quite fun to watch – Samir telling Mahmoud how to drive, how to do things, Mahmoud talking back – both like biddies, which is the way many men interact in Egypt.

Back in Bawiti, the town bustled post-Iftar – children racing about, men smoking sheesha in open-air coffee shops, grocers selling fruit and spices and opened bags of grain, covered women leading children by the hand. Dusty and crazy, it was a bit much for me after the surreal day, so I headed to the room to shower and sleep. The shower was a head hanging from the wall, basically, so the whole bathroom got wet, but a drain in the floor made it more efficient than it looked.

Anyway, before that, I asked J to get me a lemon soda and some TP from Samir. He did this on his way out to dinner at the Popular Restaurant (worthy of its own post). A few minutes later, Samir and one of the other hotel guys come knocking on the door with a silver tray holding my can of lemon soda, a smudged glass, and a roll of TP. You don’t get THAT from the Hilton, now, do you? Then to bed for me, on the mattress with the red brick foundation, surprisingly comfy after a day in the desert.

Amanda

This is the first post about our trip to the Bahariya Oasis, which yielded all matter of encounters. I’m starting with the second day. After breakfasting on feta, baladi bread, fava beans, and NesCafe in the salmon-walled dining room of the Western Desert hotel, we loaded up in the hotel’s blue jeep and admired the white flames painted on the side. J had requested that awesome jeep from Samir, the manager, and since we were basically the only ones in the hotel, he obliged. We climbed in with Samir and Mahmoud, our driver, who played Arabic music in the car all day and sang nonstop as he whipped around rocks and bumped us through the Western Desert.

Our first stop was an enormous dune not far from town – the culmination of our drive was the jeep picking up speed to make it up to the lower elevation of the dune. A dune is a miraculous thing, but there is not much more I can say except that I collected some beautiful rocks and marveled over the way the sand had smoothed crevices into them.

Next we entered the Black Desert, where the sand was covered with rocks that looked like a layer of pepper from a distance. We stopped at Black Mountain, one of the largest formations, and the rocks here were striking – obviously black, and cut, grooved, shaped by the whims of sand and wind. I climbed about ¾ of the way up the mountain (it wasn’t a big mountain, mind you) until it got too steep for my tennies. J went the other direction, down a path like a spine, picking and tossing rocks.

Again, changes – scrubby plants and lighter sand. Soon Mahmoud swerved off the main road again, and we bumped around for a bit before a large square tank appeared, water spilling into it from a pipe. Next to the tank was a hut, its walls woven with palm leaves, inside of which were mats and woven baskets. When we went to change clothes, I asked Samir if it would be offensive for me to wear shorts, and he said no, "You are free here." Ah, this is where freedom can be found, in a hot spring in Egypt. I wore a huge tee-shirt, in addition to my sprawling mesh shorts, and still I felt a bit risqué until later when an older woman showed up with a bikini bottom sporting her buttcrack. Still, I felt better in my baggy get-up, especially considering the gaze she got from the men folk.

The hot springs were not as hot as one would imagine and smelled of sulfur, but I cannot downplay the fact that this was my favorite part of the day. Water gushed from the pipe and circulated, emptying into a channel that ran to the side and eventually under the palm leaf wall of the hut and through the hut itself. When we pulled up, an old man on a donkey had stopped near the hut, and the donkey was hauling baskets of green on each side of his belly. People were working in a field in the distance, and there was a small group of homes far off comprising a Bedouin village. As we swam, the bikini-ed woman came and left with her posse of Egyptian men, and a group of American tourists pulled up, looked around, and departed.

Then Samir said they would make us lunch. As we sat on the edge of the tank to dry, two little boys walked up and asked for money. J gave them 50p and they seemed thrilled. I tried to speak a little Arabic to them, and they asked me for a pen, which I didn’t have. Kids want pens here. Bring them if you visit. The oldest boy couldn’t have been more than 6; the other was 4 or 5. This was already something we were used to – the kids, everywhere - a subject for another post. The two of them stared, fascinated, until Samir called us into the hut.

Our lunch was set up on a squat round table painted yellow. We sat on the mat-covered floor and feasted on baladi bread, fava beans in tomato sauce, soft feta mixed with tomatoes and cucumbers, tuna (J ate this), chips, Pepsi, and agua. I love me some food. It was so shady and cool in the hut, with the spring running through the channel and the palm tree foundations. When we were finishing up, Mahmoud brought us Bedouin tea in little mugs shaped like pitchers. Indescribably delicious, this tea, with fresh sprigs of mint. Keep in mind that poor Mahmoud and Samir were sitting there fasting, it still being Ramadan for a couple more days. When we finished, we washed our hands and feet in the part of the spring that ran through the hut – there was a bar of soap nestled in the palm tree closest to the water.

We left this tranquil setting and went on to a military stop, where Mahmoud had to give info about himself and say what nationality we were. We had heard from others that you are bound to get a military or police escort if you are an American tourist, and that this escort is like having a big target on you saying, Hey, Look at the Americans!, but we did not run into such trouble on our trip.

We then crossed into the White Desert, another landscape shift, and almost immediately pulled over to see Crystal Mountain, which is more like a hillock made entirely of – you guessed it – crystal. Slivers lay broken over the mountain, but this was the only site with an environmental protection sign, and you know how I am about rules, so none of you are getting crystals. But you may get a rock if you play your cards right.

From here we went off road, eventually coming upon the breathtaking panorama of a valley marking the beginning of the most interesting parts of the White Desert. We stopped here and gazed at the chalklike minerals, rippled like snowdrifts, against the side of the mountains. Then we entered the valley. Some parts of the floor were sheer rock, and Mahmoud took the jeep nearly sideways at the base of formations to stay out of the rock. We entered another large open patch with a white rock floor on which were scattered “flower rocks,” black and round with bulbous protrusions. We stopped here, and Mahmoud, having noticed my penchant for collecting the details of the earth, kept handing me rocks, each one stranger than the next.

The landscape changed again, this time scattered with shrubs and palms, many of them fallen over or dead. Samir said the Bedouins used to live here “200 or 300 years ago.” Samir was a great person to have around, but he was no historian. I soon learned to curb my questions about the history of places and just enjoy them for what I saw. What was clear was that the groves had outlived their usefulness – no water, no human life. We kept passing these old groves and turned onto a rockier landscape, the jeep shuddering as we dodged boulders. Suddenly a real oasis appeared, a small grove of palms with a natural spring. Mahmoud stopped to put water in the jeep. Someone had hung plastic bags of sugar, salt, and flour from the palm trees, which were loaded with colorful bunches of small dates.

Finally, we reached the most eerie and famous formations of the White Desert – mounds at first, like swollen thumbs dipped in salt and sugar. The first stop: “Ice Cream Valley,” consisting of scooped and swirled formations. Eventually, we came to “The Chicken,” which is two formations – one that looks like a flower or a mushroom, and the other shaped like a small hen clucking up at the flower. Both are situated on a round pedestal of rock as if they had deliberately been put on display.

Indeed, that’s the amazing thing about all of these formations – they look as if they, like the Sphinx, were purposely created and sculpted – lions, profiles of human faces, etc. – when the miracle is that they were simply made from erosion, deposits, wind – the whims of minerals and air. I guess a further miracle is that what we tend to see in these formations is ourselves.

The other day I was thinking about this tendency to see ourselves in inert objects and came upon a passage in a book called The Botany of Desire, in which Michael Pollan quotes Emerson: “Nature always wears the colors of the spirit.” In classical rhetoric, “colors” refer to tropes [this trope info was also revealed to me by Pollan], meaning that we cannot see or experience without preconceived notions, past experiences, or expectations coloring what we see. We think these formations in the White Desert imitate us rather than that we imitate them, or perhaps it goes deeper than imitation. The smallest crevice delights us only in that it seems to resemble ourselves and what we know. Sure, the desert was eerie, but the shapes were us – they could only be us.

All of this (with respect to Emerson, Pollan, DeLillo, and everyone else who has had thoughts such as this a million times before, of course) struck me when we pulled up to a formation and Samir said: “The Horse.” Even though I nodded my head in agreement, I could see nothing like a horse. I saw a large base and a smaller craggy bit jutting from the top. Meanwhile, J scrambled up a formation that seemed a bit big for his britches; nonetheless, he made it and paused like Superman surveying his heroics, chalk smattering his jeans. Then I peered at the horse and saw its long neck and its mane, exactly where I had been looking for it.

At this point, I must flash forward to the next day, when we watched the sun setting from English Mountain, a cliff with a crumbling rock house where some Brit used to live. The cliff offers a magnificent view of Bawiti and the sun, pink and dropping until it plops out of sight. We took a few pics before the sun actually set but then just watched the splendor, hands wrapped around our knees. As the sun sank, a woman behind us loudly lamented the faulty lighting of her camera, totally disregarding the miracle of the present because she couldn’t record it as a moment in the past.

Let’s go back to The White Desert, though, where the sun is beginning to set just as we pull up to a formation called “The Mushroom,” which I sit under like Alice, watching the way other formations seem to change with the light, surfacing and submerging. Iftar comes, so Mahmoud and Samir chow. Then back to Bawiti and the hotel – a two hour drive.

We met other vehicles occasionally, which each time involved a conversation of lights flicking on and off: Are you there? Yes, I’m here. Do you see me? Yes, I do. Are you sure? You betcha. And one last flicker upon passing. I might add that no one seemed to have taillights. As soon as Samir fell asleep in the front, Mahmoud lit a cigarette. Later, when he tried it again, Samir woke and made him put it out. Their relationship all day was quite fun to watch – Samir telling Mahmoud how to drive, how to do things, Mahmoud talking back – both like biddies, which is the way many men interact in Egypt.

Back in Bawiti, the town bustled post-Iftar – children racing about, men smoking sheesha in open-air coffee shops, grocers selling fruit and spices and opened bags of grain, covered women leading children by the hand. Dusty and crazy, it was a bit much for me after the surreal day, so I headed to the room to shower and sleep. The shower was a head hanging from the wall, basically, so the whole bathroom got wet, but a drain in the floor made it more efficient than it looked.

Anyway, before that, I asked J to get me a lemon soda and some TP from Samir. He did this on his way out to dinner at the Popular Restaurant (worthy of its own post). A few minutes later, Samir and one of the other hotel guys come knocking on the door with a silver tray holding my can of lemon soda, a smudged glass, and a roll of TP. You don’t get THAT from the Hilton, now, do you? Then to bed for me, on the mattress with the red brick foundation, surprisingly comfy after a day in the desert.

Amanda

Monday, October 23, 2006

Back From Bahariya

This is only a quickie. We've returned from Bahariya Oasis and we had a fabulous time. These are only a few pictures of the startling, bizzaro realm of the oasis and parts south. There are many, many more of these and plenty of stories to come. Later. For now, enjoy these.

James

Sand Dune Outside the Town of Bawiti

The Black Desert

The White Desert--just one part of the surreal landscape

Sunset on Some Other Planet

This is only a quickie. We've returned from Bahariya Oasis and we had a fabulous time. These are only a few pictures of the startling, bizzaro realm of the oasis and parts south. There are many, many more of these and plenty of stories to come. Later. For now, enjoy these.

James

Sand Dune Outside the Town of Bawiti

The Black Desert

The White Desert--just one part of the surreal landscape

Sunset on Some Other Planet

Friday, October 20, 2006

Over the past week, the weather has started to cool. It’s breezier, too, and at night, the wind contains the faintest hint of a genuine chill. Everything is less oppressive; even the sunlight, halogen-like during our initial weeks, has softened, bronze during the day, golden in the evenings. The skies are much clearer now that they have finished burning off the rice fields around the city, and my recent struggles with sore throats and mild sinus infections have disappeared. If this is a taste of winter in Cairo, I’ll have two helpings, please.

Some nights I’ll return late from campus on the Zamalek shuttle, which lets off at the dormitory, a five minute walk from our apartment. I walk up Marashli St. and turn right onto Bahgat Ali, past the Chinese Embassy and the guards who know my face by now. From above, there comes wailing laughter, a high-pitched, mocking call that begins someplace behind me and zooms past, over my head and on down Bahgat Ali. Even though it’s dark, I look up, because I look up when I hear the call of a bird, any bird, much less the chilling cry of this particular bird, which, like many birds here in North Africa, I have not seen or heard before (although the House Sparrow is exactly the same here as one I’ve seen at birdfeeders in Iowa, California, Minnesota and Ohio). But it is dark and the bird flies safely past, mocking the entire way down the block and past earshot, without my seeing it, and I am left to gaze at the wondrous maze of tree branches that meet above the road. They form a thick nexus; the trees themselves emerge from the sidewalks on both sides, leaning out slightly over the road and over me. I think it’s a beautiful sight, but when I first encountered this stretch of Bahgat Ali St., something else tugged at me…a faint recognition, a memory. A likeness to these trees elsewhere. At some point—while falling asleep or waking up, showering, teaching, perhaps during a student conference or a grade-norming session—the memory emerges from behind whatever boulder I have situated in front of it, and I am transported into a brown sedan—although, perhaps my memory does not serve the facts specifically, and I am superimposing my grandfather’s brown sedan from another memory, possibly those times when I would wake for school and he would be there, having risen at his customary 4 am and driven two hours on state routes to have coffee with my mother. His brown sedan in our driveway. What I know is that I am in a car, and he is there, and so is my grandmother. This memory is dislodged from any context and it occurs to me as perfectly distilled. There is nothing in my adult perspective to sully it or diminish it, and isn’t that so often the price of adulthood? There is no past or future action that connects this memory to any other thing. We are driving along a narrow, curvy country road in Kentucky. I know it’s Kentucky because we have crossed the Ohio River into Maysville and left that little city behind. We are surrounded on all sides by a great forest. It is vast. The trees are unlike the trees on Bahgat Ali—they are large, overgrown, wild and untamed. Occasionally a gap will appear in them, and I can look out to one side at the world I have been shielded from, and what I see is empty space. It’s easy to forget the embankment leading down to the Ohio River is just a few dozen feet from the edge of the road. Manchester blinks its blackened eye at us—and is gone. And I forgot about Manchester, just like I forget about the world. All is green and I am protected—from what I don’t know. That’s what I would like to remember. Safety implies danger. Why did I feel so safe?

I’m there now, in that world. I’m standing in the middle of the street and just an instant has passed. I don’t have any declarations to make. I’d like to sit in the back seat with myself while my grandparents drive us through the Kentucky woods and tell myself, whisper it, really, that it’s not so bad. It’s even a good thing, out there beyond the canopy of trees spanning from one side of the road to the other.

James

Friday, October 13, 2006

Today I was awoken by the Friday call to prayer. It was almost noon. I listened to the chanting and singing, the loudspeaker reverberating between buildings – at times, monotonous, at times lilting. I opened the back door and stood on the balcony, collecting laundry off the line, and the strange voice swelled and withdrew. It is still hot here, hotter than usual for this time of year. Yesterday it was 95 degrees in Cairo, while, in Illinois, my parents woke to 30 degrees and snow. Today it is 88, and the skies do not hold those dark clouds from the burning rice fields that have hovered the last few days. This week I finally put long-sleeved cotton shirts to the test. And I was no hotter than usual. See, it means something that I have been brazenly wearing my short-sleeved shirts and plastering my arms with 50 spf. Each time I look in the closet, I think about what my clothing will say about me when I step outside.

I don’t find the clothing issue too oppressive since I am a foreigner; therefore, it seems that I have more power to do what I want. If I am seen as a loose Western woman, there is little I can do to deter that, and if I were to cover my head, I would be a complete poser. But it’s weird to be a girl here. OK, foreign girl. I am almost thirty, but I must use the term “girl.” Anyway, the kinds of looks and words you get from men here have no relation to your age and are in no way to be taken as a badly-planned compliment or offensive forms of flattery because it doesn’t matter what you look like. If you are a woman, fat or skinny, flat-chested or big-breasted, you will get looked up and down and all around like you have never been looked at before.

After coming here, I met a couple of American women who said they suffer endless harassment. They said it tires them; they said they are on the verge of a nervous breakdown; they said they cannot respect this facet of this culture – the obvious inequalities between men and women. I did not quite see their point of view in the sense that I did not have such a strong reaction (which surprises me, but I think not having a strong reaction to a lot around here has kept me sane and laughing), though I wondered about it because both of them dress much more conservatively than I do. I do not dress provocatively (which goes without saying, folks), but I do not purposefully cover my arms and sometimes feel okay wearing capri-style pants and my American tennies that stick out like sore thumbs. And I usually don’t get harassment, only looks, and they really didn’t seem all that bad for a while – simply looks. I was feeling pretty good, actually, like I must look like a respectable lady and the feelings these American women were talking about were just overreactions. I generally walk with confidence and as if I have a busy sense of purpose, and this seemed to be working well for me. (Of course, the fact that I acquiesced to looking down when I walked so as to avoid catching the eye of a man – as that might seem an invitation of some sort – and the way I would defer to J doing the talking even though sometimes I was able to understand something in Arabic that he wasn’t, is in itself self-imposed harassment.) Sure, some soldiers mumbled things when I went by, and I do recall hearing a couple of hisses from men seated in front of embassies, but no one was running out and grabbing my rear or anything, and no one seemed vicious.

Then one morning J and I were looking for a taxi when a man on a bike passed us, turned around, cupped his hand against his man-breast as he looked at me, then pointed at J and gave him the thumbs-up. He also said something in Arabic that was obviously dirty, probably “Nice melons” or something equally repulsive. He kept repeating the cupping motion and his thumbs-up. Why was J getting props for MY assets? Huh? Shouldn’t my great-grandma Glasco, beautifully buxom, get credit for this? I gaped in disbelief while J sternly told the man in Arabic to get the hell away. The only thing that would have made this incident into a good story is if that man would have run his bike into a parked car, flipped over the car, then been pummeled by stray cats. As it was, I was at first astonished that this was happening at 10 in the morning, then, as we finally hailed a cab and the driver spoke pleasantly in English to us, I felt humiliated.